By INA ALLECO R. SILVERIO

Bulatlat.com

Bulatlat.com

MANILA — Allan is only 17, but he has been working full-time since he was 10.

“It’s back-breaking work, but I do it because I want to help my family. Food is expensive, life is expensive. It’s really hard when you’re not rich,” he said.

Allan lives in Caraga, Northeastern Mindanao and is a farmworker in one of several palm oil plantations in the province, the Agusan Plantation Incorporated (API). He works eight hours a day doing different jobs in the plantation, from harvesting to hauling and loading. He is thin and lanky, but there’s a look of strength in his hands. When standing, he maintains a straight posture, but once sitting, the curve in his back becomes noticeable. There is weariness in his eyes, a look of exhaustion that one does not expect from someone so young. He said that working in the palm oil plantation is a difficult life, but he has known no other existence but one surrounded by poverty. He was able to attend up to second year high school before he stopped and worked full-time.

Then there are children like Jayson, Jerald, Junfil and Jonny, aged 18 to 22. They are also like Allan who work in plantations, but stopped schooling much earlier, ending their formal education at grade five. Others like Racquel, Joseph and many others who have been working since they were five.

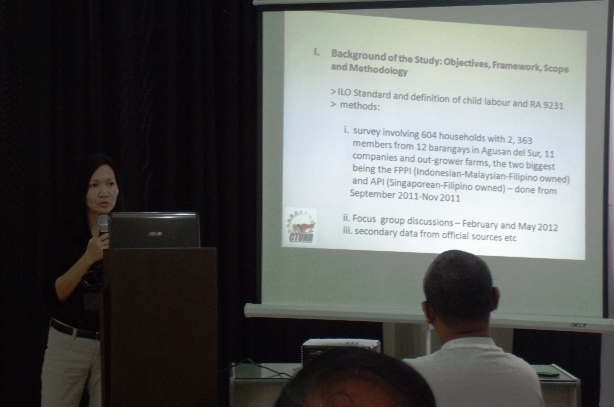

Daisy Arago, CTUHR executive director, shares the results of their research on child labor in palm oil plantations.(Photo by Ina Alleco R. Silverio / bulatlat.com)

Daisy Arago, CTUHR executive director, shares the results of their research on child labor in palm oil plantations.(Photo by Ina Alleco R. Silverio / bulatlat.com)It is their lives and the conditions they have been exposed to from such an early age that the labor and human rights institution Center for Trade Union and Human Rights (CTUHR) documented in its new research titled ” Children of the Sunshine Industry.” The results of the research were presented in a public forum on October 4 at the Sto. Domingo Church in Quezon City. The research delves into the situation of child workers and laborers in oil plantations in Caraga. In attendance were Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU) leaders, CTUHR president Sr. Emelina Villegas, Fr. Quirico Pedregosa of the Church-Worker Solidarity (CWS) network and Commissioner Jose Manuel Mamauag of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR).

Poverty from cash crop palm oil

The palm oil industry in the Philippines began in the 1950s , first in Zamboanga, then in the 1960s in Sultan Kudarat. Came the 80s, plantations were established in Agusan del Sur. There are currently 54,748 hectares devoted to palm oil planted lands in the Philippines, 55 percent or 17,252 hectares are found in Caraga, primarily in Agusan del Sur.

Acording to latest reports, the Benigno Aquino III government aims to expand the coverage of the plantations to 62,500 hectares, and to 200,500 hectares by 2016.

The Aquino government and promoters of palm oil industry claim that there are many benefits to developing the palm oil industry because there is a huge export market in China, India, Pakistan, the United States and Europe.

Palm trees have a higher yield than most crops like bananas, pineapples or coconuts. It requires a shorter gestation period, and is the source of large quantities of non-food by-products and biomass for organic fertilizer, biogas, bio-energy.

The government and agencies such as the Philippine Palm Oil Development Council (PPODC), the Caraga Oil Palm Development Council (COPDC) and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) assert that palm plantations enable farmers to secure higher incomes, reduce rural poverty and provide thousands of jobs for the rural poor.

Palm oil has many uses. Some 80 percent of all palm oil sources are for edible use. It has no cholesterol and easily digestible. It contains vitamin E, and it is used in the production of margarines, vegetable ghee, spreads, confectioneries, and non-dairy products. It is said to be the best oil for frying, and it is also an important raw material in the production of oleochemicals, fatty acids, fatty alcohols, glycerol, and other derivatives for the manufacture of cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, bactericides, and other household and industrial products.

Commissioner Jose Manuel Mamauag of the Commission on Human Rights shares his reaction to the research while Fr. Quirico Pedregosa of the Church-Worker Solidarity (CWS) network (leftmost side), Sr. Emelina Villegas, CTUHR chairwoman and Lito Ustarez of Kilusang Mayo Uno listen. (Photo by Ina Alleco R. Silverio / bulatlat.com)

Commissioner Jose Manuel Mamauag of the Commission on Human Rights shares his reaction to the research while Fr. Quirico Pedregosa of the Church-Worker Solidarity (CWS) network (leftmost side), Sr. Emelina Villegas, CTUHR chairwoman and Lito Ustarez of Kilusang Mayo Uno listen. (Photo by Ina Alleco R. Silverio / bulatlat.com)For all the value of palm oil, however, and the claims made by those who promote the massive land conversion of lands formerly devoted to rice and other staple food crops, the palm oil industry is under attack for countless human rights and labor rights violations. The CTUHR’s new research exposes yet another side of the operations of the industry: the use of child labor.

Children of the palm oil industry

CTUHR executive director Daisy Arago said they used the standards of the International Labor Organization and provisions of RA 9231 An Act Providing For The Elimination Of The Worst Forms Of Child Labor And Affording Stronger Protection For The Working Child, Amending For This Purpose Republic Act No. 7610, As Amended, Otherwise Known As The “Special Protection Of Children Against Child Abuse, Exploitation And Discrimination Act as guidelines for analyzing the conditions of the plantation farmworkers in Caraga region. The research also made use of secondary data from official sources such as government agencies.

The labor rights institution conducted a survey involving 604 households with 2, 363 members from 12 barangays in Agusan del Sur. The respondents — all farmworkers and their children, work in 11 companies and out-grower farms, the two biggest being the Filipinas Palm Oil Plantation, Inc or FPPI (Indonesian-Malaysian-Filipino owned) and the API(Singaporean-Filipino owned). The survey as well as the focused group discussions were conducted from September 2011-Nov 2011 and February to May 2012 respectively.

The CTUHR’s survey covered the work conditions of child laborers and adult workers in the API/Agumil and FPPI-NGEI (nucleus plantations) and the out-grower plantations Karaga Farm, Uraya, Kuftrinco, Lubrico, Armelle Jay, Galo, St. Joseph, Serano and Webina Farms.

Of those surveyed, 36.4 percent are children between 5 to 17 years, 46.8 percent are of working age (18 years old) and 12.4 percent are below five years old. Arago said it was “shocking” to learn that based on their survey, 24 percent of workers in palm oil plantations are children.

“They’re so young, yet they’re already engaged in hard labor. At their age, they should be in school, or playing, enjoying their childhood. They should be spared from hardship, but because their parents are poor and they live in a situation of capitalist exploitation, they are forced to grow up early,” she said.

Based on the survey, boys comprise a large majority of child workers at 77 percent, while the girls account for 22.6 percent. Some 72 percent of all child plantation laborers in Agusand del Sur live in five barangays: Manat in Trento,Tagbahan, Ebro, Maligaya and Mati in Agusan del Sur.

“Like their adult counterparts, child workers engage in various plantation work activities; they work as fruiters, harvesters, haulers, kickeralls and as uprooters. Harvesting is one of the most strenuous activities as children have to use a long and heavy steel rod with a scythe at the end with which they cut the fruit from the tree. Loading is also very difficult,” Arago explained.

She said child laborers carry 15 to 45 kilos of fresh fruit bunch (FFB), referring to the palm fruit which grows in bunches or big clumps like bananas. Each child worker carries two to three bunches on their back with each trip from the harvest area to the pick-up point where the fruit bunch and loose fruit are weighed and loaded on a truck.

P25 to P150 for eight hours hard labor

There are no laws governing the work hours of the child laborers. Most of them or 85 percent of all those surveyed said they work for eight hours every day. Some (a small five percent) work part-time or below eight hours. The remaining percentage work for as many as 12 hours daily.

“For a moment let us pretend that child labor is already given. Imagine that these children work as hard as their adult counterparts, but they also earn as little. Eighty-six percent of the child laborers who work full-time in the plantations are paid below the minimum wage. Like most of their adult counterparts, they are casual workers — never signing contracts, never receiving benefits from the company,” she said.

Arago said a hauler is paid P3.00 ($0.07) for every bunch he hauls, regardless of how heavy it is. Harvesters are also paid P3.00 ($0.07) for each bunch they harvest, but his income doesn’t increase even if he harvests more than 50 bunches.

“This means he has to haul at least 50 bunches a day to earn at least P150 ($3.57). Only 10 percent of the surveyed child workers earn the minimum wage, while the remaining four percent earn above the minimum,” she said.

At the time of the study, the minimum wage for plantation workers in the region was pegged at P231 a day ($5.50) or P6,006 ($143) a month for 26 days of work. The amount the child workers receive, however, differ. Of those surveyed, 36 percent of those paid below the mimum only get P4,500 ($107) a month. Thirteen percent receive P3,000 ($69.67) a month and about 10 percent get P4,000 ($95.23) a month. The rest get only P2,500 ($58.14) and even less for a month’s work.

Loose fruiters are paid differently. A child laborer is paid P5.00 to P8 .00 ($0.12 to $0.19) per bucket of loose fruit, which contains five kilos. In a day if he is able to fill the average five buckets, he receives P25 to P40 ($0.60 to $0.95) for an eight-hour work day.

Arago said that considering the nature of work and the price of the fresh fruit bunch per kilogram, the already below-minimum wage rates (particularly of the harvesters and haulers) do not make a slightest dent in the company or farm’s production costs and expenses. The minimum quota some companies like the API impose is 45 fresh fruit bunches a day.

Arago said that considering the nature of work and the price of the fresh fruit bunch per kilogram, the already below-minimum wage rates (particularly of the harvesters and haulers) do not make a slightest dent in the company or farm’s production costs and expenses. The minimum quota some companies like the API impose is 45 fresh fruit bunches a day.

“We used the conservative price workers at a palm oil milling plant gave us to compute the profits of palm oil companies. It came out that companies get a 92.75 percent profit from each fresh fruit bunch. This means that the company or farm pays only the cost of three bunches for every worker who harvests even up to 50 fresh fruit bunches a day,” she said.

An fresh fruit bunch weighing the minimum 15 kilos sells at P86.25, ($2.053) at P5.75 ($0.13) per kilo. Deduct from this the P6.00 ($.0.14) paid to the harvester and the hauler. The difference of P80.25 ($1.91) goes to the company, excluding other costs like rent and processing; this is equivalent to 92.75 percent of the value of the fresh fruit bunch and the oil extracted from it.

In the survey, it was found out that 74 percent of the children in the 5-17 year-old age group attend school, and 38 percent are in the lower years from kindergarten to third grade. Forty percent attend the the fourth to six grade; 15 percent are in high school, from the first and second year levels. Sadly, 71 percent of all those who attend school end up reaching only the fifth grade.

Backbreaking work

Child workers in the plantations are also exposed to many occupational hazards. Most of them, unsurprisingly, suffer from fatigue and minor injuries.

“Some have experienced having a fruit bunch fall on their heads, or suffering cuts that bleed badly because of the sharp thorns of the bunch. They consider these ‘minor injuries’ because, as the children said, they can still get up, stand and walk after getting hit by a fruit bunch or cut by thorns,” Arago said.

Based on the research, 68 of the 97 interviewed child laborers have been injured at work, 41 percent of them had minor injuries. Some of those who were practically stabbed with the thorns fall sick with fever. Others said they slipped and fell on slopes and rolled down with the heavy baskets loaded with fruit bunches they carried. Of those surveyed, five percent said they have had bone fractures.

“But even when they are feeling ill with aching bodies, feet and backs, child haulers, loaders and harvesters still report to work. Not going to work automatically means no money on the days they were absent,” Arago said.

Child laborers like their adult counterparts in the Agusan plantations are not provided with safety shoes, gloves or goggles. They wear only long-sleeved shirts, pants, and rubber slippers. If they get injured, the companies only give out paracetamol tablets and the “no work, no pay” policy is strictly enforced regardless of whether the failure to report to work was caused by an accident at the plantation.

“Some of the children — seven percent of those interviewed — said that they have had eye problems. Loose fruiters — or the ones who collect loose fruit — in particular, are susceptible to the herbicides sprayed around the circular base of the palm trees. As they pick the loose fruit with their bare hands and standing on uncovered feet, they come into contact with the pesticides that also spread to surrounding grass and leaves,” said Arago.

A vicious cycle

Based on the CTUHR’s research, child laborers are hired in a myriad of ways, but primarily they begin their work on the prodding of their parents who are also farmworkers.

“Can we blame these parents? Do we report them to the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD)? Their own parents were also child laborers before them. Neither parents nor children have known any other life but poverty. There are barely jobs in many areas in Caraga, the eight poorest region in the country. The incidence of hunger in the region is also quite high at 47 percent of the total population as per 2009 statistics. There is a serious lack of social services like public health, housing and education. People there grit their teeth and bear the daily hardships they suffer. Children from an early age are taught that,” Arago said.

Arago said it is precisely the poverty of the parents that make child labor a severe and widespread phenomenon is areas like Caraga and the rest of the Philippines.

“There’s mass unemployment and lack of access to means of livelihood in the region. The palm oil industry only contributes 1,400 jobs, but every worker has to cover eight to 10 hectares on a regular basis.

Needless to say, adult workers also receive low, below minimum, wages just like the child laborers. The immediate and direct consequence is the families’ limited capacity or inability to send their children to schools. This in turn already clips whatever potential they have for better economic opportunities. It’s a vicious cycle,” she said.

Hold companies accountable

While the palm oil industry is being hailed by the Aquino government to be a sunshine industry, it does not shine upon the lives of the plantation workers who earn starvation wages, or on the lives of the children it illegally employs.

“The high number of child workers in the areas we surveyed indicates the continuing underdevelopment of the communities in the areas within and surrounding palm oil plantations. To end child labor in palm oil plantations, parents — the workers — must be given the means to provide for their children and the entire family,” Arago said.

Arago said that with the help of the Kilusang Mayo Uno (KMU), the Church-Worker Solidarity network and the rest of the human and labor rights community, the CTUHR will launch a campaign to push for the implementation of legally-mandated minimum wages and benefits for all workers in Caraga palm oil plantations and in the other regions.

“This is one way to put a stop to child labor — by easing the economic burdens of the parents, and by pressuring the palm oil companies to stop violating minimum wage laws. These companies should also be exposed for violating countless occupational health and safety standards. Finally, the fact that they hire child laborers is also a serious violation: they are more accountable than the parents who would never have sent their children to work if they earned enough to keep their children in school,” she said.

In the meantime, children like Allan work and wait, and the palm oil industry in Caraga continues to make money from their lost childhood.

No comments:

Post a Comment